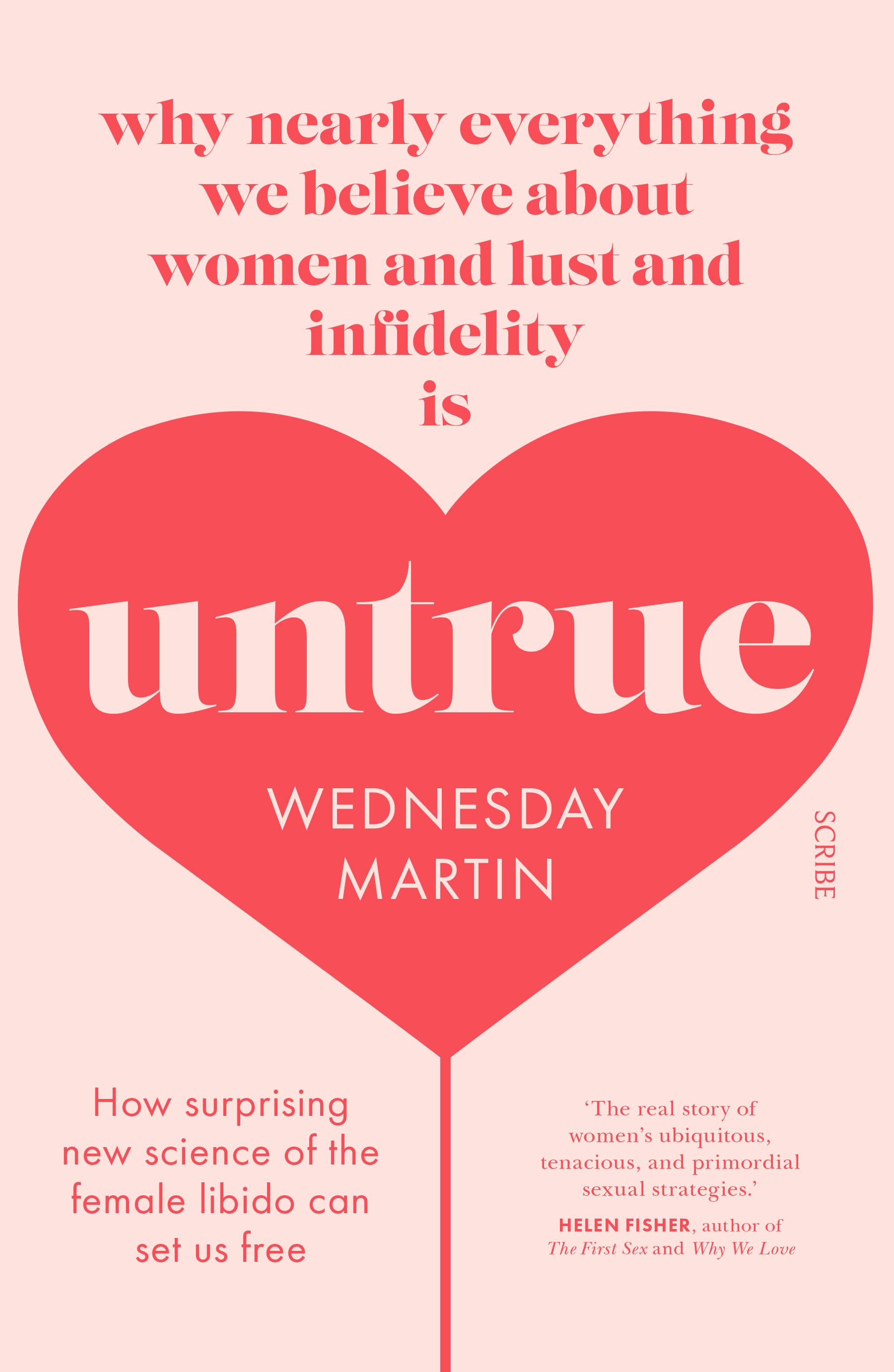

Untrue

Wednesday Martin

I wasn’t sure what to wear to an all-day workshop on consensual non-monogamy.

It was a typically disappointing early spring morning in Manhattan, rainy and colder than you’d hope. The program I was attending was designed for mental health professionals but open to curious writers and everyday citizens like me who paid the $190 fee.

Maybe I was overthinking things as I stood in front of my cramped closet, considering my options. But this keenly felt need not only to find something appropriate to wear but to be appropriate, and at the same time a little rebellious, reminded me of all the bargaining we do with ourselves about monogamy. I stared at blouses and trousers and dresses and thought of the big concessions we make and the little ones, and of the greatest trade-off of all, in which we surrender complete, dizzying sexual autonomy and self-determination for the security of the dyad. This conundrum—I must extinguish the part of me that lusts for a universe of Others in exchange for the ability to raise kids, get work done, and sleep through the night without obsessing about what exactly You, my One and Only Other, are up to while we’re not together—is the beating, bleating heart of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents and much else written on the topic of coupling for life. Relinquish your libido, or tame it, for stability. Somehow we presume this is a developmental imperative of sorts, the hallmark of maturity and health, and that it will be easier for women, that it comes “naturally” to them.

Was there any way around this particular compromise, with its implicit assumptions about gender and desire? Maybe today I would learn something new from people trying to circumvent it. I imagined them—the pointedly and deliberately non-monogamous, and those there to support them—as ninjas in sexy black jumpsuits and aviator style sunglasses, stealthy, well versed in self-defense, and exceedingly limber.

I settled on a floral blouse, a red coat, and black jeans. At the last minute, I also put on some bright red lipstick, because it was Friday, and I was going to a workshop on consensual non-monogamy, even though I kept transposing it, every time I told someone about it, into a workshop on “non-consensual monogamy.”

“You just told me a lot,” a psychoanalyst friend had quipped when I flipped things around just so as we chatted. A heavy patient load had prevented her from signing up for the workshop. “Have lots of anonymous encounters for me!” another shrink friend who couldn’t make it for the same reason texted me the morning of, winkingly conflating shrinks who help swingers with swingers. And sex addicts. “Poor Joel,” my literary agent ribbed in faux sympathy with my husband when I told him of my day’s mission. I was learning over the course of many months of talking to people that infidelity, promiscuity, non-monogamy, whatever terms we use to describe the practice of refusing sexual exclusivity, fascinates and flusters pretty much across the board.

And I knew from prodding and poking and reading and interviewing and from just being female that the specter of a woman who is untrue still raises hackles and blood pressures and outrage especially, all along the spectrum. For social conservatives, female infidelity—seizing what is generally believed to be a male privilege, doing what you want sexually speaking—is symptomatic of larger corruptions and compromises of the social fabric. (“Madam: What a decadent, pathetic woman you are. You don’t have to wonder why the west [sic] is in decline; just look in the mirror,” a self-described “traditionalist media personality” emailed me after I had written a piece on female sexuality.) Among progressives, especially those who describe themselves as “sex positive,” female sexual self-determination may be tolerated, even lauded. But in their world, a woman who has an affair is still likely to be considered or called something much worse than “self-determined” for having done so. (The echo chamber of obsessional Hillary hatred from supporters of both Sanders and Trump demonstrates that the Left can be as triggered by the idea of female autonomy in general as the Right.) Meanwhile, many advocates of “disclosed” non-monogamy believe transparency is best, and that cheating by men and women alike is unethical. But with the accreted layers of history and ideology, it’s hard to carve out a space where there isn’t a particular pall hanging over the woman who creeps and lies, even within these apparently enlightened arrangements. Everyone, I learned, seems to have a point of view about the woman who refuses sexual exclusivity, whether she does so forthrightly or on the down-low.

Talking about my work could up the awkwardness quotient at cocktail parties. Plenty of people were eager to ask me about and discuss female infidelity. About as often, it brought the conversation to a halt. After a few uncomfortable exchanges, I decided it was easier to tell people that I was writing a book about “female autonomy.” It seemed considerate to deploy a half-truth about an uncomfortable reality in order to spare those who might not really want to discuss it. And to sidestep any ire or judgment directed at me by association when I said the “I” word. “Some of us have been on the receiving end of that,” more than one man told me dourly, as if it were reason enough for me to write about square dancing instead. A colleague with whom I could be frank about my work and whose opinions I trusted looked at me across his desk and offered, “A shrink I know told me all women who cheat are crazy.” At a dinner party, I asked an until-that-moment perfectly charming couples therapist for his informed view on non-monogamy. “Those people are . . . unwell!” he sputtered. Those around him—well read, well thought, considered and considerate—agreed, citing “disease” and “instability.” “He studies healthy people, and your topic is unhealthy people,” a woman said amiably, as if this were a given. And this was a friendly crowd. When I spoke about my work with female friends and acquaintances, I often floated the notions that compulsory monogamy was a feminist issue, and that where there is no female sexual autonomy, there can be no true female autonomy. This was met with everything from enthusiastic agreement to complete confusion—what did monogamy and infidelity have to do with feminism?—to denunciations of women who stepped out as “damaged,” “selfish,” “whorish,” and, my favorite, “bad mothers.” By self-described feminists.

But the most common responses by far when I spoke about my topic were “Why are you interested in that?” and “What does your husband think about your work?” The tone ranged from pointedly curious to accusing, and the implication was clear: researching female infidelity made me, at the very least, a slut by proxy.

But I suspected that these people today, the ones at the workshop, would be different.

“Working with Non-Monogamous Couples” was held at a nondescript family services center in a nowhere neighborhood between Midtown West and Chelsea. (I later learned that it fell within what was once called “the Tenderloin,” Manhattan’s entertainment and red-light district in the late-nineteenth to early-twentieth centuries, and that the particular street had once housed a row of brothels. Reformers had referred to the area as “Satan’s Circus” and “modern Gomorrah.”) The center’s building was near a sushi restaurant and a handbag wholesaler. Having attended a talk in the same series (“Sex Therapy in the City”) in the same venue about a year before, I knew I would be surrounded by therapists who were there for certification credits and to learn from an expert in their field about the best approaches to issues that were likely to come up in their work. I also knew a little bit about consensual nonmonogamy: I knew that it was for people who didn’t want to be monogamous, and who didn’t want to lie about it. It was presumably for “consenting adults,” which made it sound a little sexy and a little unsexy and clinical at the same time.

As I checked in with Michael Moran, one of the program’s organizers—a high-energy, friendly psychotherapist with chic, short salt-and-pepper hair—he observed that whereas in previous years he had mainly worked with gay men for whom nonmonogamy “was often more or less a given,” he had recently noted an uptick in his practice and in general of heterosexual couples seeking solutions to their monogamy quandaries.

“It’s pretty incredible that people commit for life, that they get married, without even discussing the issue of sexual exclusivity,” I offered by way of chitchat, realizing as I said it that my husband and I had committed for life, that we got married, without even discussing the issue of sexual exclusivity. Monogamy and marriage, for straight people in much of the US, go together like a horse and carriage. Or they used to. Or maybe not. After many months of research and interviews, seeing headlines like “Is an Open Marriage a Happier Marriage?” on the cover of the New York Times Magazine, attending Skirt Club parties where avowedly straight, frequently married-to-men women had one-off sexual encounters with other women, and chatting at Open Love cocktail parties and other mixers for those in the polyamory community, I was no longer sure. Things were changing, but it was hard to gauge how much and how fast and how comprehensively. After all, the signs can seem bewilderingly contradictory. For example, a single niche, TV, has seen a quick uptick in series on non-monogamy. These include Showtime’s Polyamory: Married and Dating; TLC’s Sister Wives, about a polygynous patriarch and his four wives; HBO’s You Me Her; and the web series Unicornland, about a young female divorcee in New York City exploring her relationship options with different couples. Then there’s a counterpoint, the seventeen-season success Cheaters. The latter show’s premise is irresistibly simple, like Candid Camera for the not so candid: “dispatch a surveillance team to follow the partner suspected of cheating and gather incriminating video evidence. After reviewing the evidence, the offended party has the option of confronting the unfaithful partner.” This roster of shows dramatizes a contradiction: our country’s enduring emphasis on policing and enforcing “fidelity” precisely as it comes up against an impetus to redefine it.

A glance at the bookshelves in the “relationships” section of any bookstore confirms that something is indeed afoot. Reads like How Can I Forgive You?, Getting Past the Affair, When Good People Have Affairs (a title that suggests we generally think they don’t), and Transcending Post-Infidelity Stress Disorder long predominated. But of late, there are books providing alternatives to the Ultimate Devotion/Ultimate Betrayal narrative we Americans cleave to when it comes to monogamy and infidelity. And they are popular. Opening Up: A Guide to Creating and Sustaining Open Relationships by Tristan Taormino is a perennial seller. So is The Ethical Slut, a how-to for the woman who wants to get sex outside of monogamy in a way that is principled, nay virtuous (it seemed all my divorced girlfriends and friends in their twenties were reading it). In The New Monogamy, Tammy Nelson, a guru for those who struggle with the issue of sexual exclusivity, deftly redefines monogamy as a frequently difficult practice, like yoga, that requires commitment. She also suggests we think of monogamy as a continuum, encompassing everything from “You can’t look at porn because that’s a betrayal” to “You can sleep with others, but our relationship has priority.” Esther Perel’s Mating in Captivity and The State of Affairs, along with the work of psychoanalysts Michele Scheinkman and Stephen Mitchell, all challenge our expectation that our partners can and should be everything to us—co-parents, companions, confidantes, and lovers. Scheinkman suggests that rather than presume we are failing at marriage when we can’t make this “being all things” business work, we might consider the “segmented model” of marriage that exists in Europe and Latin America, where it’s understood that marriage will fulfill some needs but not others. Affairs and marriage are separate domains in some of these contexts, and affairs are more likely to be presumed “private” than “pathological.” Scheinkman critiques what she calls the “dogmatic no secrets policy” that tends to prevail in our fifty states of affairs and in the therapy sessions where we try to work things out with partners.

As if to describe this recent shift in our thinking, the emerging idea that lifelong sexual exclusivity might be up for reconsideration, sex and relationship advisor Dan Savage, the openly gay and unsparing critic of what he sees as the hypocrisies of compulsory monogamy in the US, coined the term “monogamish” to describe a committed relationship that allows for forays with others. Savage asserts that monogamy is a tough racket, that we need alternatives, and that gay men gentrified non-monogamy for straight people, sort of like they did the Upper West Side and all of San Francisco. But how extensive are the renovations to the house that monogamy built, really? In 2000, experts reported that roughly 95 percent of respondents in a statistically representative sample of cohabiting and married American adults expected monogamy of their partners and believed their partners expected it of them. Australian researchers presented a nearly identical statistic in 2014. Sociologist Alicia Walker, who has studied infidelity extensively, observed that in spite of changes in the sociosexual landscape, “studies and polls routinely find that Americans disapprove of infidelity for any reason . . . [and] the cultural mandate against it is so strong that no one wants to admit to being cheated on, or to be the person who publicly says we don’t think cheating is so bad.” Will there ever be Starbucks and Bugaboo strollers in the edgy, exciting neighborhood of Monogamish?